After the British East India Company established a trading post in 1819 and solidified its grip through The Treaty of Friendship and Alliance in 1824, Singapore was placed “firmly under the control of the British”. Vast areas of primary forest were soon cleared to cultivate cash crops. While plantation agriculture has ceased in Singapore, the land use patterns set during this time have shaped the natural landscape of Singapore as we live and experience it today. Yet, much of the historical narrative of these plantation economies, particularly regarding the labour and resources that sustained them, is recorded and told through the colonial gaze. This history often omits and neglects inconvenient narratives and excludes the realities of those who lived and worked on and around these plantations.

“a seed, a shift and a lost pineapple” brings together Cheong See Min, Madhvi Subrahmanian and Marvin Tang to explore how contemporary artists are rediscovering and responding to these absences and biases through their research and artistic practice. By centering the voices that are missing from these histories, the exhibition raises questions around the decisions that have shaped our relationship to the land today, and more broadly, the politics of remembering—namely, who does the remembering and who gets to be remembered.

In his long-term research project “The Colony”, Marvin Tang investigates how botanical institutes shaped the movement of seeds, plants, and people in the colonial era. The project’s first chapter focuses on the Hevea brasiliensis, also known as the Pará rubber tree, as a reflection of Singapore’s early relationship with the botanical empire and the terraforming of natural landscape through the colonial plantation economy. Originating from Brazil, the Hevea brasiliensis was transported over 17,000km away from its native land to the Malaya peninsula, where it became a major cash crop in the region in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tang’s 2021 work, The Tree That Bleeds White Gold, examines this history through the story of Henry Wickham, who was commissioned to smuggle rubber seeds from Brazil to Kew Gardens, leading to the rubber seedlings’ eventual arrival in the Malaya peninsula. Filmed entirely in Singapore, where rubber trees can still be found in our secondary forests and parks, the video makes visible this history of thievery and movement that catalysed rubber plantations in the region. The rubber seedlings were brought to Singapore in the Wardian Case, an instrument used for plant relocation and that inadvertently facilitated the displacement of both plant and people as by-product.

Tang constructs three of such replica cases, one from his residency at NTUCCA in 2020–2021 and two as part of On Glazed Cases series, to examine how this product of abnatural ecology echoes through our natural history and landscape up-close. Tang’s critical examination of these histories probe at the profound ecological and social transformations wrought by colonial ambitions in the plantations, and invite reflection on the hidden forces and apparatus behind what made these decisions possible.

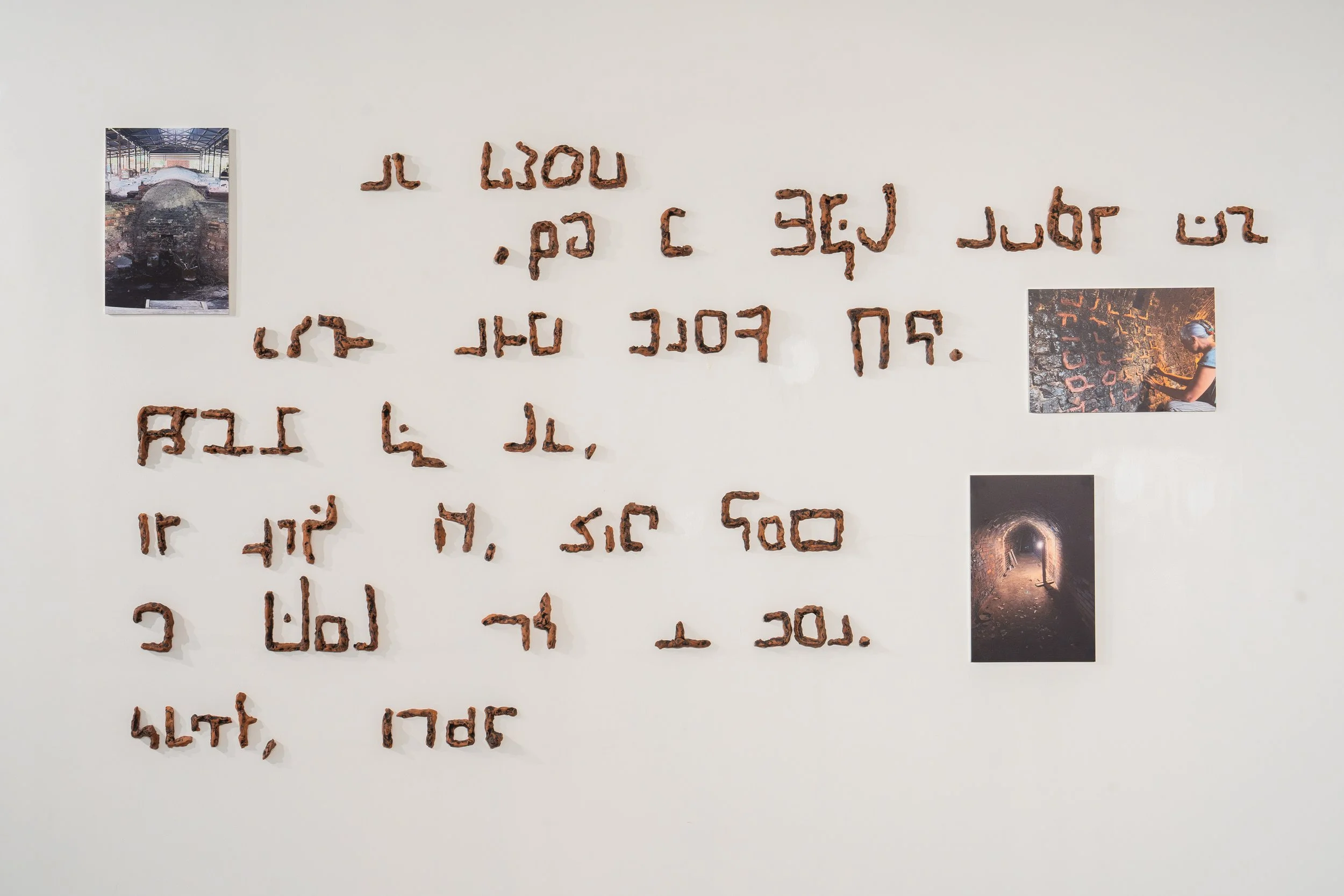

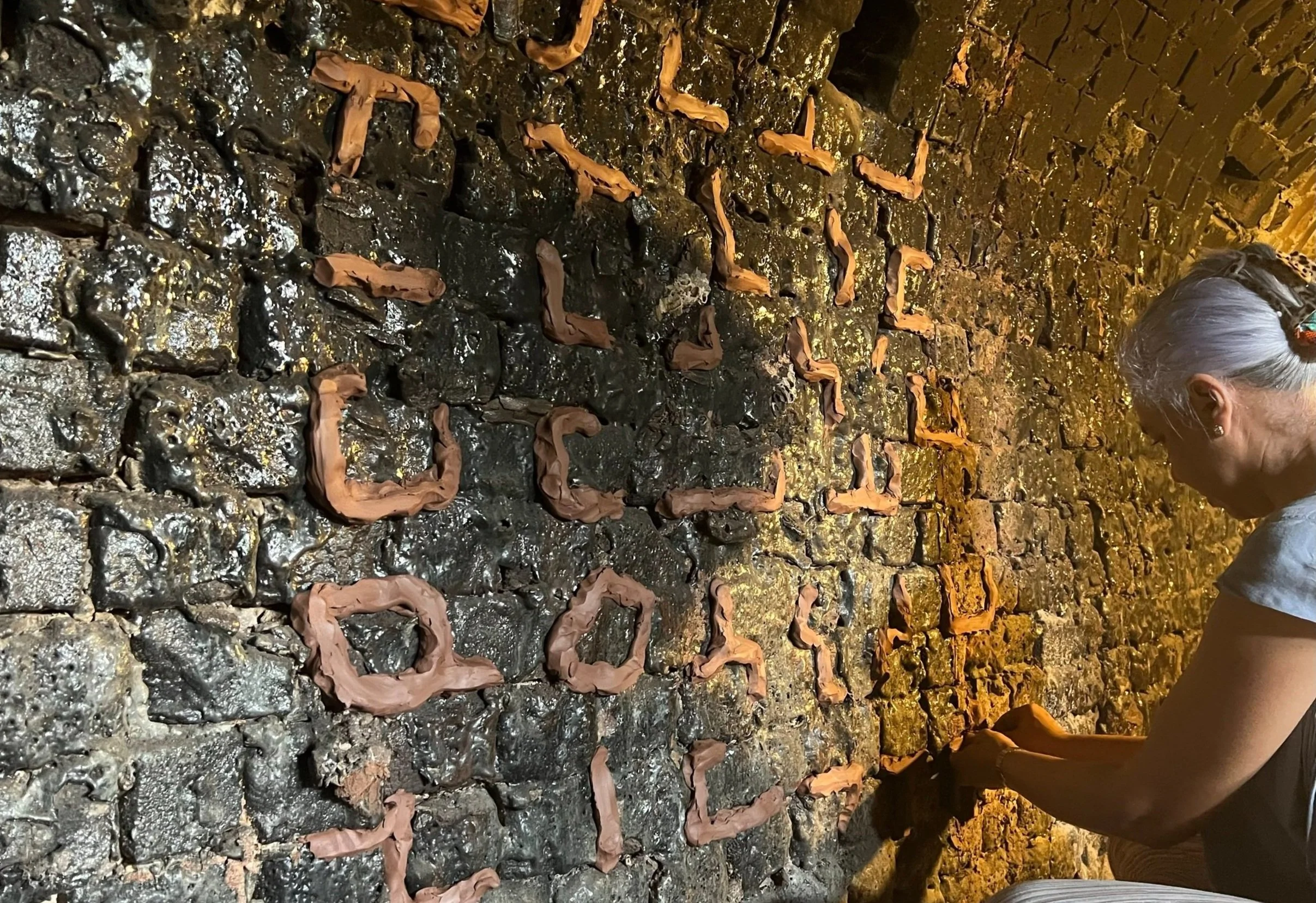

In A Letter From the Past (2023), Madhvi Subrahmanian examines the Guan Huat Dragon Kiln’s association with rubber plantations from the last century. This historic kiln in Jalan Bahar, one of the only two remaining dragon kilns in Singapore, is a brick-built wood-firing kiln that stretches 43 metres long. In its prime, the kiln was fired fortnightly to meet the demands for latex cups needed by rubber plantations in surrounding areas. While now dormant, the interior of the kiln is marked by cracks and encrusted glaze from extensive firing and ash, serving as testament to the hard and extensive labour that worked around the kiln.

Subrahmanian’s installation takes the kiln as an extension of the plantation to consider how labour and resources were structured even outside of the fields to serve this economy. She employs soft clay to fill the cracks in the kiln, allowing forms shaped like a cryptic script to emerge, stringing together an imprint and a message from the past.

This also builds on her earlier work, Ode to the Unknown (2017), an installation of archival images of labourers and rubber tapping cups. The artist created new cups at the Guan Huat Dragon Kiln to pay homage to the labourers–the original unnamed makers and users of the rubber tapping cup. This work is in the permanent collection of the Indian Heritage Centre.

Cheong See Min delves into histories of plants, fibres and textiles that were exported from Malaysia to English during the British occupation, drawing from rigorous archival research as well as family history with relatives who had worked on plantations to uncover overlooked perspectives on these plantations. Her research on gambier, a plant native to Southeast Asia and once an important trade item in 19th century Singapore and Johor, highlights the environment and labour costs of its cultivation.

Gambier was the earliest recorded plantation in Singapore and saw high demand from England and the Americas as a good source for tanning leather and dyeing textiles in the 1830s. The crop, however, takes a significant toll on land as it exhausts the soil drastically and renders it infertile after about 15 years.

In addition, the purification of gambier required so much firewood that forests surrounding its plantations were stripped of wood for fuel. Despite all this, gambier continued to be cultivated to feed European demand. The result was a pattern of “shifting cultivation” which started from the Singapore River area and eventually spread across the island until practically all viable land had been exploited. By the 1860s, Gambier planters moved to Johor to repeat the same pattern.

In Cheong’s Where Is the Gambier Plant? and Shadow_Gambier, she hints at this lesser-known history of the crop. Cheong also investigates the colonial history of the pineapple leaf fibre industry, which was established through the labour of Chinese coolies and turned a South American plant into a significant export from the Malaya peninsula in the 19th century.

Her residency at Gasworks in London, supported by The Institutum, culminates in A cart of lost pineapples, a handwoven textile artwork referencing an archival image of a buffalo cart loaded with pineapple on a journey to the Singapore dock. Through her work, Cheong draws critical attention to the natural and human resources expended in these plantations.

Cheong See Min (b. 1994, Malaysia) is a multidisciplinary artist currently practicing between Malaysia and Taiwan. Her practice interrogates the relationship between human nature and the tropics. She considers weaving an act of communication that mediates between past and present. Her works have been featured in exhibitions internationally, including “Communities in the Making”, esea contemporary, (2023), and The International Biennial Exhibition of Micro Textile Art, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine (2021). She was recently artist-in-residence at Rimbun Dahan in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (2022) and Gasworks, London, United Kingdom, supported by The Institutum.

Marvin Tang (b. 1989, Singapore) uses image as a tool of investigation. His research questions the linearity of historical narratives and the notion of collective identities. He is a recipient of the Photoworks Prize at the London College of Communication in 2018. His works have been shown in DECK Centre for Photography in Singapore, Thessaloniki PhotoBiennale in Greece, Jimei X Arles International Photo Festival in China, among others. He is a Producer at Superhero Me, a neurodiverse multidisciplinary collective based in Singapore, and lectures at ADM and Lasalle College of the Arts.

Madhvi Subrahmanian (b.1962, India) was born in Mumbai and currently lives and works in Singapore. Her practice explores the performative intersection between sculpture and installation and is informed by her consistent engagement with the sensuous materiality of clay. Subhramanian’s focus predicates the possibilities and challenges of meditative multiples and immersive installations, through which she contemplates the ever-changing concepts of space and place. She has exhibited in numerous international exhibitions, including: Gyeonggi International Ceramic Biennale, South Korea (2019); Indian Ceramics Triennale, Jaipur, India (2018), and The First Central China Ceramic Biennale, Henan, China (2016).

Clara Che Wei Peh is an independent curator and art writer in Singapore. Her research and practice focus on new media, emerging technologies, and the intersections of art and money. She was recently Curator for Art Dubai Digital 2023 and Guest Curator at ArtScience Museum, where she co-developed, “Notes From the Ether” (2023). Her work has been published on Yishu: Journal of Chinese Contemporary Art, Asian Art Biennale Reader, The Brooklyn Rail, Hyperallergic, The Art Newspaper, among others. She was a member of Shanghai Curators Lab 2023 and is currently a Asia Collection Fellow at KADIST.