Blk 7, 1st Floor, Gillman Barracks

Curated by Karin Oen

“国破山河在

~春望 (杜甫)

Countries may fall,

Mountains and rivers remain”

The history of ink painting, and specifically landscape painting (called shanshui, mountain and water) in Chinese culture is often most associated with refined aesthetics and historical points of reference that connect ink practitioners across time and place. Elements of style including realism, archaism, naturalism, and abstraction intersect with symbolic cultural coding. Ink, and the human creativity and insights that are expressed through its material properties, has remained critical to Chinese art practices in modern and contemporary times.

In the early 20th century, calligraphy and ink painting remained vital, and political – part of a wider conversation on the modernization of Chinese culture and art that saw the evolution of the term guohua (national painting) to distinguish ink painting from Western oil painting and other art media with foreign origins. This lineage is also entwined with the primal materiality of this substance and the elements of wood, fire, and water that are involved in its creation, and the material intelligence involved in making and handling ink.

Ink holds a central place in Chinese history, inexorable from the written word, the painted line, and the culture of the literati. In addition to key historical records, works of literary art, and examples of visual mastery created with ink as a medium, ink itself, and the methods of making ink have a prominent place in Chinese culture. One example, the Qimin Yaoshu – a Northern Wei dynasty encyclopedic text on Chinese Agriculture written by the scholar-official Jia Sixie in the 6th century – outlines best practices for cultivating things basic to human survival: planting and growing grains and fruits, raising livestock, preserving and cooking food, and making ink.

Not just the domain of Confucian scholars, ink was valuable for all. The ingredients to make ink were relatively simple, but the text stressed the need for them to be of high quality. The recipe starts with carbon in the form of soot from burnt wood or lampblack from burnt oil which was mixed with glue then repeatedly pounded (at least 30,000 times, according to the Qimin Yaoshu), rolled, and thinned with steam or water before it was pressed into molds and allowed to dry in carefully controlled conditions. The ink sticks then await being ground down into powder on an abrasive ink stone and reconstituted with water for specific uses and effects.

Song dynasty painter Guo Xi explained the multiplicity of inks required to execute landscape paintings: “Use burnt ink, ink that has been kept overnight, receding ink, ink made from fine dust. One is not sufficient. You cannot achieve the desired effects through only one ink… sometimes you use light ink and sometimes dark, sometimes scorched, kept or receding ink. At times you use ink made with soot from the stove and at times ink mixed with blue in a diluted form.”

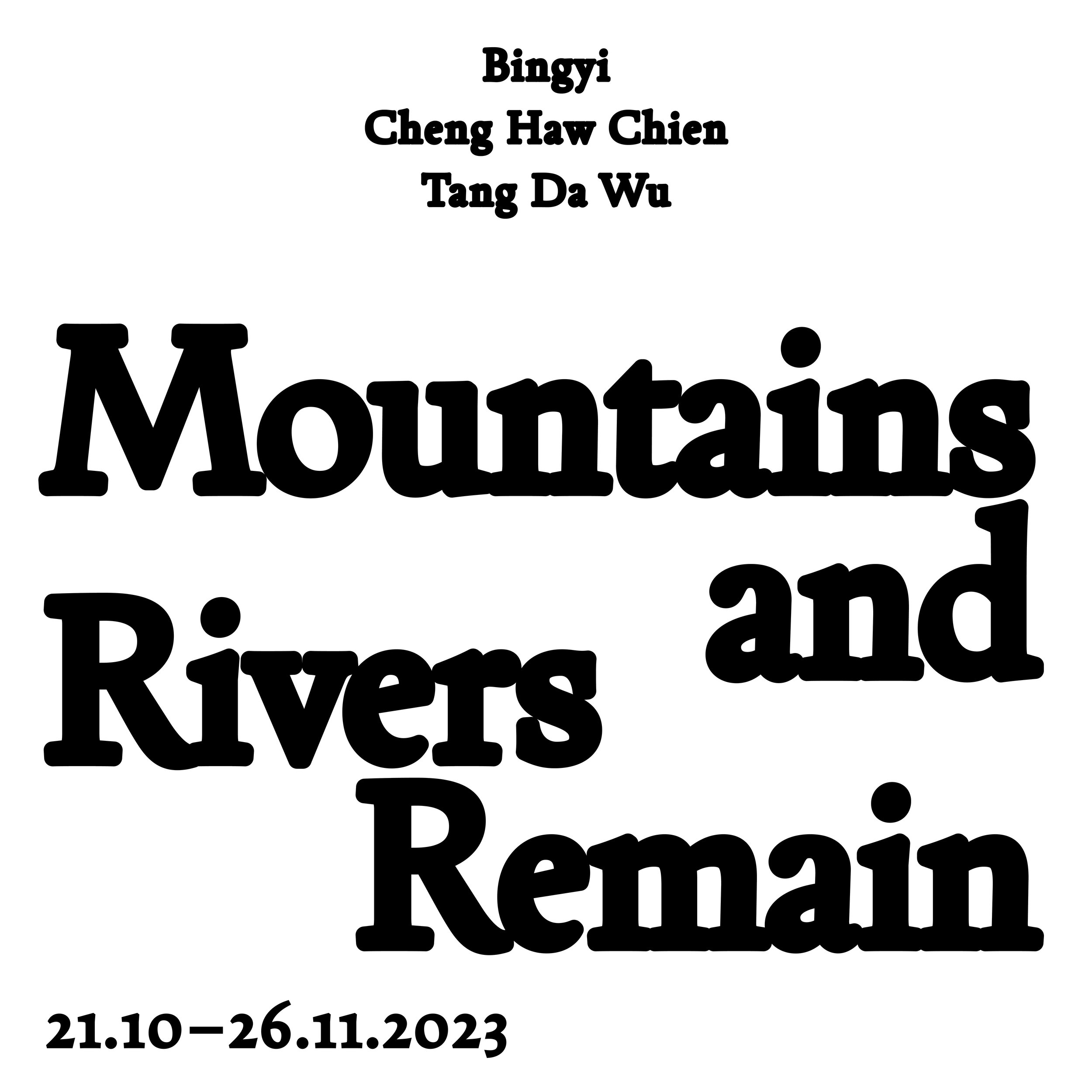

This exhibition of contemporary painting takes its title from Spring View by the Tang dynasty poet Du Fu, and presents work by Bingyi, Cheng Haw Chien, and Tang Da Wu, three contemporary artists whose work relies on the material properties and expressive potential of ink. Each artists’ work simultaneously mines the rich history of ink painting and the embedded importance of ink itself – a substance that is at once prosaic and alchemical, historical and contemporary.

Rather than putting these artworks in conversation with specific historical Chinese landscape artists or movements, this presentation offers the work of these three distinctive artists as current manifestations of an enduring engagement with the elements of landscape mediated by the material of ink itself, framed with some historical figures’ notes on ink, landscape, and life. These artists are part of different generations and practice in different corners of the world – China, Malaysia, and Singapore – showcasing both the contemporary diversity within the medium of ink and discernable areas of overlap and synergy.

Tang Da Wu’s abstract ink paintings reveal a side of this artist’s practice that complements his collaborative, conceptual, performance, sculpture, and figurative works. By working with dampened paper, Tang creates ink work that traces the motion of the ink that he manipulates on the surface, and the movement of ink as it seeps and bleeds into the paper itself. Sometimes deeply pigmented, sometimes only lightly tinged with ink, his paintings allow for the viewers to see a wide range of mark-making techniques, including washes, stains, and lines formed through creases or folds. In the hands of Tang, these seemingly simple compositions reveal the live, unpredictable quality of working with ink, gesture, and chance. The exhibition’s opening, featuring a live ink painting performance, offers the public a window into these processes:

“I might say something wrong or do something silly in front of my audience, but you cannot change it. That is so precious for an artist. That is so real.”

In the works of Prof Cheng Haw Chien, we see an artist’s dedicated revisitation of mountains - from the Himalayas to China, to Australia and beyond – in paintings of different scales and employing different degrees of abstraction. A contemporary proponent of the Lingnan style of painting and a former student of Master Chao Shao An (Zhao Shao Ang), Cheng combines aspects of perspectival rendering with his deft use of calligraphic brushwork and splashed ink techniques, all brought together by the spiritual and energetic inspiration of his subject matter. Equally dedicated to poetry and calligraphy alongside painting, Cheng has cultivated the skills and talents of a literati scholar and then synthesized them in his lifelong dedication to studying nature and traveling as sources for his art.

Bingyi’s Streams and Mountains series offers another incorporation of literati principles into compositions that reveal the deep tonalities of ink. Also a poet and student of Daoist philosophy, Bingyi adds ink to water, marking the paper with the water’s motion and relationship to wind, gravity, temperature, humidity and other natural forces. Realized in the Taihang Mountains, on the eastern edge of China’s Loess Plateau, these paintings are a collaboration between the natural conditions, the artist, and the ink and xuan paper. An extended and painstaking process of painting follows the initial exposure of ink and paper, where the artist adds dozens of layers of ink with a fine brush over the course of a year or more.

Mountains and Rivers Remain, 2023. Bingyi, Cheng Haw Chien, Tang Da Wu. Image courtesy of The Institutum

Photography by jonathan tan

Bingyi (b. 1975, Beijing) is a Los Angeles-based artist, writer, film-maker, curator, cultural critic, and social activist. Over the past decade, she has developed a multi- faceted practice that encompasses land and environmental art, urban planning, site-specific architectural installation, musical and literary composition, ink painting, performance art, and filmmaking. Adopting a non-anthropocentric perspective and channeling nature’s creative agency, her work is centrally concerned with the themes of ecology, ruins, rebirth, and poetic imagination. After pursuing university-level studies in biomedical and electronic engineering in the United States, Bingyi earned a Ph.D. in Art History and Archeology from Yale University in 2005 with a dissertation on the art of the Han Dynasty.

Bingyi has exhibited internationally, including at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (2022), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2021), the Brooklyn Museum (2019) the National Art Museum of China (2017), Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art (2016), Gwangju Biennale (2008), and has executed monumental performance projects at the Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport and Toronto City Hall.

Professor Cheng Haw Chien (b. 1948) was born in Penang, Malaysia and lives and works in Kuala Lumpur. He began learning Chinese brush painting and western art forms as an adolescent, subsequently continuing his studies in Taiwan, where he met many renowned artists including Zhang Daqian, and Hong Kong, where he studied with Master Chao Shao An, a late proponent of the Lingnan School’s fusion of Western, Japanese, and Chinese painting elements. He studied calligraphy and poetry under the Venerable Chuk Mor (Zhu Mo) and Liu Taixi.

His extensive international travel is reflected in his landscape work, exemplified by a 1981 world tour to Australia, New Zealand, the Pacific island nations, Central and South America, the United States, Canada, Europe, Africa, India, Nepal, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, and the Philippines. Prof. Cheng was appointed principal of the Central Academy of Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, in 1983 and has exhibited his paintings and calligraphy widely, including at the National Art Gallery, Taiwan, and the Palace Museum, Beijing.

Tang Da Wu (b. 1943) lives and works in Singapore. Prior to formally studying art, Tang enjoyed drawing and actively practised painting while learning from more established painters. Following his first solo exhibition of drawings and paintings in 1970, Tang sought to further his artistic pursuits by studying abroad in the UK. After returning to Singapore, Tang began to work in performance art, and in 1988, he co-founded The Artists Village, a collective committed to promoting experimental art through the provision of studio and exhibition space.

In 1999, he was awarded the Arts and Culture Prize at the 10th Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize and in 2007, he represented Singapore at the Venice Biennale with artists Zulkifle Mahmod, Jason Lim, and Vincent Leow. Through the course of his career, Tang has exhibited at important platforms, including the 1st Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale (1999), 3rd Gwangju Biennale (2000), and The Artists’ Congresses: A Congress at Documenta13, Kassel, Germany (2012).

KARIN OEN is a curator and art historian based in Singapore where she is Senior Lecturer and Head of the Department of Art History at NTU’s School of Humanities. She works on historical, modern, and contemporary creative practices related to the transcultural and the transmediatic. Recently, Karin was Deputy Director of Curatorial Programmes at NTU CCA Singapore and co-editor with Ute Meta Bauer and Tan Boon Hui of the 2022 book SEA: Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia, commissioned by the Institutum and published by Weiss Publications, Berlin. Karin is a graduate of Stanford University (BA), Christie’s (MA), and MIT (PhD).